Media Literacy in the Age of Disinformation

By: Joshua Glick

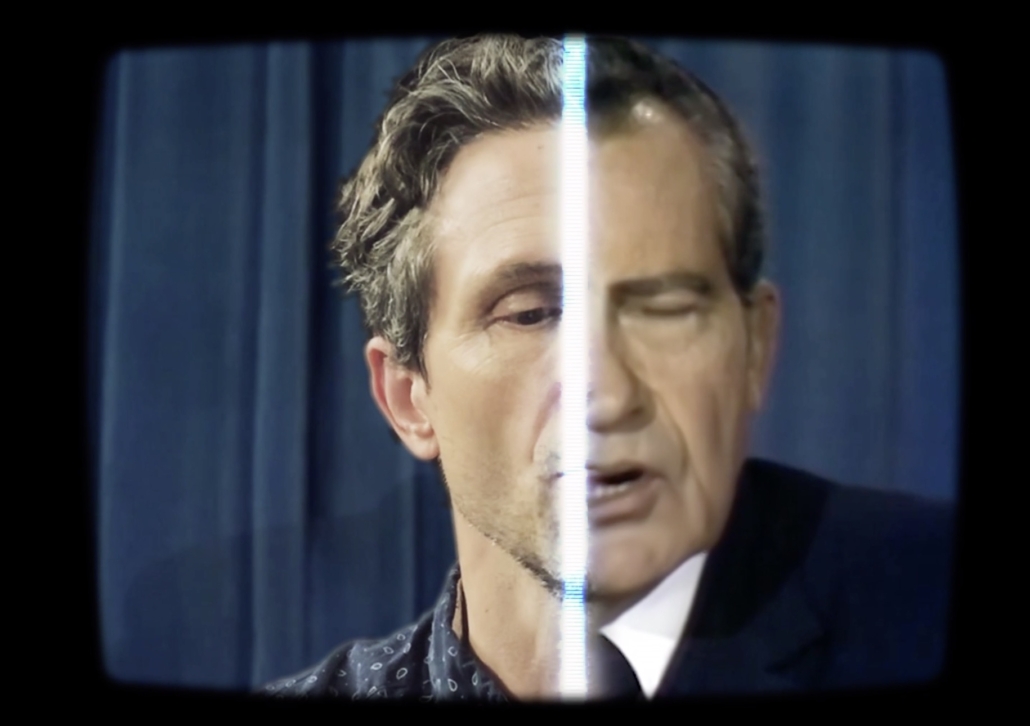

In Event of Moon Disaster is a deepfake video that was designed to be both an art installation and a pedagogical tool. It demonstrates the urgent need for media literacy education in an age of sophisticated disinformation. Produced within MIT’s Center for Advanced Virtuality and premiering at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, the video features a compilation of re-cut television footage of the 1969 lunar launch as well as an AI-generated Richard Nixon reading the contingency speech his administration had prepared in case the mission failed.

Teaching In Event of Moon Disaster as a case study within a media literacy curriculum highlights the dangers of disinformation as well as the importance of trustworthy media to the preservation of democracy. These concerns are more timely and relevant to students than ever: In an era of rising authoritarian populism, accompanying crackdowns on legitimate journalism outlets, and grassroots calls for environmental and racial justice, citizens need both credible information and a better understanding of how to engage with this fragmented media environment.

While media literacy initiatives vary widely across K-12 and college classrooms, they tend to focus on a constellation of interpretative practices, equipping students with the tools necessary to explore how different forms of media are created, used, and interpreted.[1]

As a new and innovative form of malicious persuasion, “deepfakes” (a phrase that combines “deep learning” and the aim to deceive) use artificial intelligence to simulate peoples’ actions or utterances, presenting as real things that never actually happened. The most common and easiest-to-create deepfakes involves digitally placing a celebrity’s face onto another individual’s body. Other, more complex kinds of synthetic media such as In Event of Moon Disaster use a more nuanced combination of real and AI generated media. In this case a person delivers a speech that never occurred.

Since their emergence in late 2017, deepfakes have quickly moved from the realm of celebrity pornography to world entertainment and politics. Deepfakes threaten to disrupt elections, generate damaging rumors, and compromise the security of businesses.[2] As they continue to grow more common and become easier to produce, their consequences will intensify.

Media literacy, of course, cannot provide a magic antidote to the tremendous upswell of disinformation. As a core pedagogical strategy, however, it can help students cultivate their inner critic, transforming them from passive consumers of media into a discerning public. Teaching deepfakes means teaching about the pernicious threat they pose, the various approaches to combating them, and the alternative uses of synthetic media. This effort consists of four complementary modes of inquiry: historical awareness, fine-grained interpretation, contextual research, and co-creative production.

These modes draw on the disciplines of information and library science as well as communication; however, equally important are the analytic practices that stem from humanities fields such as cinema and media studies, English, and history.

Here are an array of options for bringing emerging media and the topic of deepfakes into the classroom.

1. The Long History of Deepfakes

I would recommend first positioning them in a centuries-long history of disinformation, including staged hoaxes, forged documents, and doctored images. Invite students to share examples.

- What are some forms of intentionally altered media from either the present or past of pop culture?

- How did they know the artifact had been altered? For what reason?

Constructing a timeline helps to contextualize the hazards of deepfakes as part of a broader and ongoing cultural phenomenon, rather than as something unprecedented or unique.[3]

Historicizing deepfakes also de-escalates alarmist rhetoric and hyperbolic headlines proclaiming their potential to usher in an “infopocalypse” or “the collapse of reality.” As Witness’s Sam Gregory notes, the inflated language so often used to discuss deepfakes “fuels their weaponization.”[4]

At the same time, it’s valuable to highlight the specificity surrounding media change. The emergence and popularization of deepfakes during the mid-2010s was shaped by developments in AI, the expansion of social media platforms, and increasingly close connections between digital tech and electoral politics. Presenting the recent rise of deepfakes in this way helps students understand that new media are not simply “invented” by individuals in a vacuum, but emerge by way of multiple, intersecting forces.

Mural of “real” and “fake” thumbnail portraits from the Witness Media Blog, part of their collection of deepfake resources. (Credit: Face Forensics database)

2. Analyzing key examples

Consider collectively diagramming individual case studies. Fine-grained analysis can serve as a powerful method of deepfake detection, particularly for low-tech, quickly made “shallowfakes” or “cheapfakes.” Play a video twice through, asking students to take notes on anything that seems “off” or strange. The third time through, annotate the viewing experience, pointing out tell-tale signs of manipulation such as lack of blinking, visual anomalies in the mouth or neck, glitching between movements (especially when slowed down), shifting facial features (patches of irregularly smoothed or wrinkled skin), and erratic patterns of light and shadow.[5]

Taking In Event of Moon Disaster as an example, an instructor might ask students:

- What makes the video persuasive?

- What, if anything, seems to indicate tampering?

Close viewing reveals that there are indeed some changes in Nixon’s vocal frequency (as if it was compressed at a low bitrate) as well as numerous tremors at the conjuncture point between the neck and head.

Of course, scrutinizing a video is by no means a sure method of detecting manipulation. Deepfakes are getting better by the day at eliminating these frictions. In Event of Moon Disaster itself, upon multiple viewings, appears convincing! Thus, as a crucial step towards assessing the veracity of a particular video, it’s essential to look at the broader configuration of images, texts, and sounds that surround it on screen, to essentially treat the webpage as a composition to be interpreted.

- Does the video have a clearly stated author?

- What is the URL and who is the host?

- Is it produced in-house by an organization or does it appear on a social media platform?

- Does the video appear elsewhere on the Internet, and if so, in what context?

- Are there other sources that corroborate the performance?

The sequence at the end of In Event of Moon Disaster as well as the larger suite of contextualizing resources on the website (including the “Interactive Behind the Scenes“) lay bare the process of its construction. They point the spectator towards the pitfalls and hazards of deepfakes in a more nuanced fashion.

Follow-up exercises where students independently compare deepfakes with authentic media, and then share their findings in small groups with their peers, reinforce slow looking and listening habits. Overall, exploring editing techniques, lighting schemes, sound design, framing information, and spatial relationships between objects heightens students’ understanding of how deepfakes are made. It also hones their ability to draw on a vocabulary in articulating how aesthetic form and style orient viewers towards specific subjects while forcing them to confront the limits of what the eye and ear can detect.

3. Combating the threat

A third method might involve a research assignment focusing on a wider breadth of strategies for combating deepfakes. Students would learn about the multi-pronged effort to fight disinformation by exploring some of these different approaches. Digital forensics involves image and audio processing software (FaceForensics, InVid, DARPA’s MediFor) that analyze content to detect computational manipulation. Verification techniques include apps (ProofMode, TruePic) and journalistic initiatives (New York Times, Google New Initiative, First Draft) that use encrypted digital “signatures” to authenticate legitimate representations. Policy advocacy entails creating or organizing around industry guidelines and governmental legislation to regulate deepfake production and prohibit unethical or illegal uses of deepfakes.[6]

Investigating these respective strategies and presenting them in class to their peers would allow students to practice accessing, evaluating, and citing different primary and secondary sources. It would also help familiarize students with key debates in the field.

- What should be the role of the government in regulating the country’s media infrastructure?

- How might platforms be held more accountable for the media they distribute?

- What are effective ways to democratize technologies that can detect deepfakes?

- How to best strengthen local and community journalism outlets?

Presentations offer an opportunity for students to share their findings, learn from their peers, and weigh in on how to revise or expand a particular approach.

4. Producing media for the public good

A fourth and final learning module might ask students to imagine and design a prototype of media that would serve the public good. Working in teams, they would think through the ethical stakes of possible digital projects. One example would be for students to research the Apollo 11 mission and create their own video essay about what happened based on primary and secondary sources. Such an assignment would not simply be a matter of teaching students to create a “true” account of the event that contrasts the “false” narrative of the deepfake, but to understand how history is not found, but made. It also highlights how the access to and assessment of sources is critical to the construction of historical narratives.

Alternatively, a class might opt for making projects focused on synthetic media. These might range from crafting data-rich predictive modules that improve systems of emergency response, health care, and urban infrastructure, to making simulations of historical events and speeches for educational purposes.

The small-group configuration would encourage students to become aware of the power of collective intelligence, working collaborative, and experiencing the kind of socio-professional interactions they might later encounter crewing on films, working in labs, writing articles, or conducting field research.

In Event of Moon Disaster actor, Lewis D. Wheeler, is transformed into President Nixon (Credit: Dominic Smith)

The Path Forward

It is hard to imagine that deepfakes might one day be eradicated. As the technology continues to improve, they will become easier to create and tougher to identify, and they most certainly will not be defeated by a “killer app” or by masterful honing of the human sensory apparatus.

That does not mean, however, that as educators we should give up.

Instead, we should continue to address this threat in the classroom, teaching students critical thinking, research, and production-focused skills. We also need to continue treating deepfakes more holistically, as part of a broader and rapidly changing landscape of disinformation. If our students begin to see media literacy not as a set of static competencies to be acquired or knowledge to be consumed, but as a constant, ongoing civic act of interpretation, we will have accomplished much. If we empower them to conscientiously engage and reorient this technology for the public good, we will have accomplished even more.

Lede photo credit: Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online, Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis, Data & Society 2017 – Treatment: Halsey Burgund

[1] Media literacy is taking a more prominent place within interdisciplinary liberal arts courses on contemporary citizenship, civics, and politics, as well as stand-alone modules and research methods classes. For the breadth of approaches to media literacy, see the white papers and special reports published by professional consortia (Association of College & Research Libraries), education advocacy organizations (Media Literacy Now, National Association for Media Literacy Education), and foundations and think tanks (Alliance of Democracies Foundation, Knight Foundation, Data & Society, First Draft, Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society). For monographs on media literacy in the age of disinformation, see, for example, Donald A. Barclay, Fake News, Propaganda, and Plain Old Lies: How to Find Trustworthy Information in the Digital Age (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018); Paul Mihailidis, Civic Media Literacies: Re-Imagining Human Connection in an Age of Digital Abundance (New York: Routledge, 2018); W. James Potter, Media Literacy (New York: SAGE Publications, 2018).

[2] For more on the technology behind deepfakes and their recent rise, see, Witness and First Draft, “Mal-uses of AI-generated Synthetic Media and Deepfakes: Pragmatic Solutions Discovery Convening” June 11, 2018; Witness Media Lab’s initiative, “Prepare, Don’t Panic: Synthetic Media and Deepfakes” includes a series of overview articles, studies, and resource kits on the subject.

[3] Robert E. Bartholomew and Benjamin Radford, The Martians Have Landed! A History of Media-Driven Panics and Hoaxes (New York: McFarland, 2011); James W. Cortada and William Aspray, Fake News Nation: The Long History of Lies and Misinterpretations in America (New York: Rowan and Littlefield, 2019); Kevin Young, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2017); Lee McIntyre, Post-Truth (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018).

[4] Sam Gregory in conversation with Craig Silverman, Episode 7, Soundcloud, Datajournalism.com, May 2020; Charlie Warzel, “He Predicted the 2016 Fake News Crisis. Now He’s Worried About an Information Apocalypse,” BuzzFeed News, February 11, 2018; Jackie Snow, “AI Could Send Us Back 100 years When It Comes to How We Consume News,” MIT Technology Review, November 7, 2017; Franklin Foer, “The Era of Fake Video Begins,” The Atlantic, May 2018.

[5] Ian Sample, “What Are Deepfakes and How Can You Spot Them,” The Guardian, January 13, 2020; Jane C. Hu, “It Is Your Duty to Learn How to Spot Deepfake Videos, Slate, June 27, 2019; Craig Silverman, “How to Spot a Deepfake Like the Barack Obama-Jordan Peele Video,” BuzzFeed, April 18, 2018; Samantha Sunne, “What to Watch for in the Coming Wave of ‘Deep Fake’ Videos,” Global Investigative Journalism Network, May 28, 2018; Haya R. Hasan and Khaled Salah, “Combating Deepfake Videos Using Blockchain and Smart Contracts,” IEEE Access 7 (2019): 41596-606; Gregory Barber, “Deepfakes are Getting Better, But They’re Still Easy To Spot,” Wired, May 26, 2019.

[6] Melissa Zimdars and Kembrew McLeod, eds., Fake News: Understanding Media and Misinformation in the Digital Age (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2020); Robert Chesney and Danielle Keats Citron, “Deep Fakes: A Looming Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National Security” 107 California Law Review 1753 (2019); Tim Hwang, Deepfakes: Primer and Forecast, NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, May, 2020.