Why We Made This Deepfake

By: Francesca Panetta and Halsey Burgund

Lots of people have asked us, as the directors, why our project—a video that purports to show an alternate reality in which the 1969 lunar landing failed, and President Richard Nixon mourned the loss of two iconic astronauts—isn’t misinformation itself. Aren’t we just adding to the many conspiracy theories about the moon landing?

Our answer to this is an emphatic no. As multimedia artists and journalists who have worked for a decade within a shifting media landscape, we believe that information presented as not true in an artistic and educational context is not misinformation. In fact, it can be empowering: Experiencing a powerful use of new technologies in a transparent way has the potential to stay with viewers and make them more wary about what they see in the future. By using the most advanced techniques available and by insisting on creating a video using both synthetic visuals and synthetic audio (a “complete deepfake”), we aim to show where this technology is heading—and what some of the key consequences might be.

Actor, Lewis D. Wheeler, being filmed delivering the contingency speech. All studio photos by Chris Boebel.

Having created complex interactives, virtual reality experiences, and audio augmented reality platforms from scratch, we initially thought it would be easy to create a deepfake. Usually we painstakingly code and construct our projects ourselves, as we are both sticklers for detail. But this time we were going to farm out the work to artificial intelligences (AIs). We could sit back, relax, and have the work done for us by a clever, highly trained black box.

We were wrong.

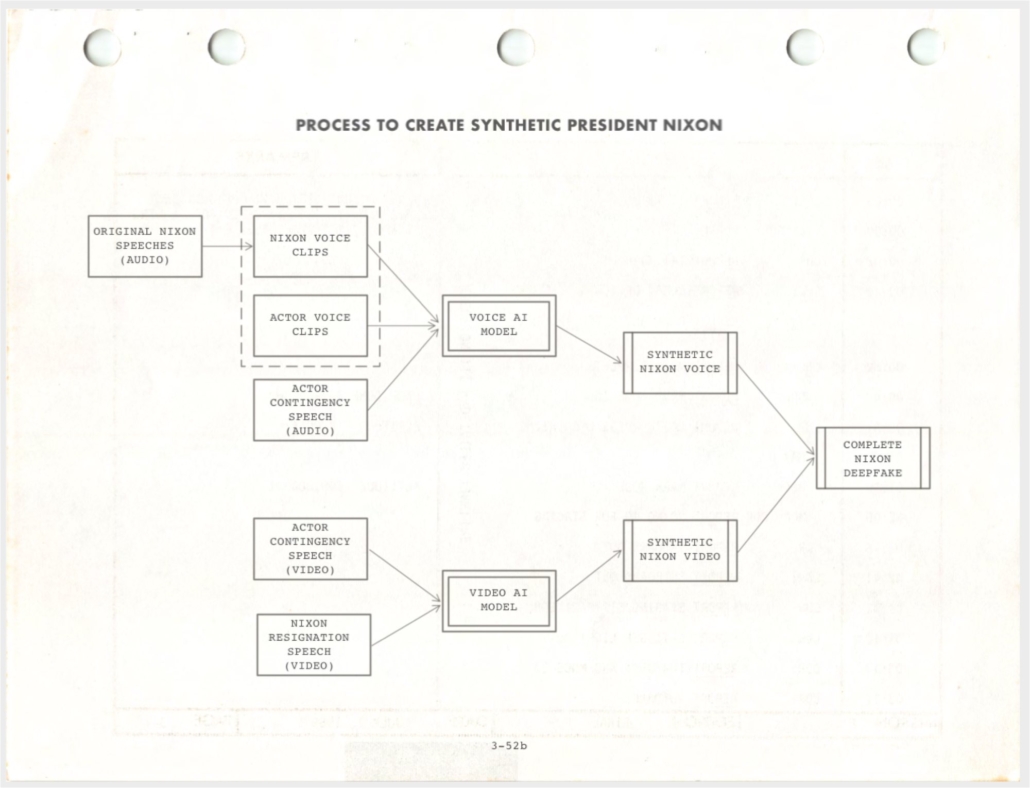

First it wasn’t one AI, but two AIs. The first was to build a model for the visuals — to make Richard Nixon look like he was in the Oval Office reading the speech, and make his lips convincingly mouth the words he never spoke. The second would build the synthetic Nixon voice so that the words emanating from his perfectly moving lips would sound and feel like Nixon was delivering them himself.

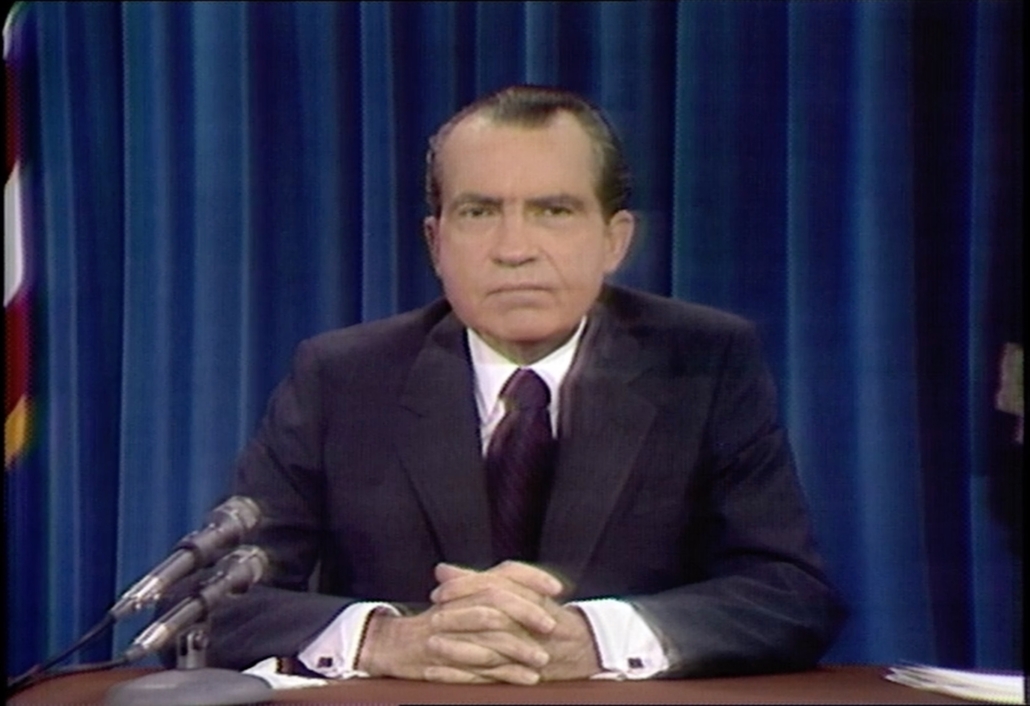

Video still from President Nixon in the Oval Office delivering a speech on the Vietnam War. (Credit: White House)

We did our research and selected two companies to work with: Canny AI, an Israeli company that does Video Dialogue Replacement, and Respeecher, a Ukrainian startup specializing in speech-to-speech synthetic voice production. Canny primarily uses its technology to lip-sync content dubbed into other languages and reduce reshooting costs. Respeecher sees its technology being used for historical reenactments and in Hollywood productions.

We got to work.

Visuals Production

For the visuals, the first step was to pick a video of a real speech given by the real Richard Nixon that we could use as a starting point. Then, we would replace his mouth motions with those of him delivering the contingency speech. Our deepfake video would effectively be this video with the mouth motion changed and audio replaced, along with some of Nixon’s suit, his neck, and his chin.

Actor, Lewis D. Wheeler, delivering the contingency speech in the studio

So if Nixon blinked in the original speech, he would blink in our deepfake; if he looked down to his script in the original tape, he would look down in ours. “What about the mouth?” we asked Omer Ben Ami at Canny AI. “Whose mouth would you see?” “You will see Nixon’s mouth, but moving as though it was delivering the contingency speech,” he replied.

We scoured hours of Nixon’s Vietnam speeches, looking for a two-minute clip in which his gestures and movements lined up perfectly with the contingency speech recording made by our actor. Page turns, head movements, hand motions needed to align believably with our new speech. We ended with Nixon’s resignation broadcast. It has the framing of the flags, a great zoom-in, and Nixon was visually showing emotion.

President Nixon delivered many different speeches in the Oval Office from which we selected the resignation speech as our “target” video. (Credit: Dominic Smith)

Audio Production

Now for the voice. We knew we would need to produce a large set of training data for the AI to use to generate our synthetic voice. Respeecher told us we’d need to find an actor willing to listen to thousands of tiny clips of Nixon and repeat each one with the same intonation and timing. We would play a clip to our actor and then record him saying it. When we were happy that the intonation was good, we would go to the next. We would do this over and over again until we had two to three hours of parallel data recorded.

Actor, Lewis D. Wheeler recording Nixon clips for training materials

“What kind of actor do we need to book?” we asked Dmytro at Respeecher. “Could I do this?” Fran volunteered. “No, a Brit won’t do. The actor needs to have a similar accent and ideally would be male,” he told us. The actor didn’t need to be the same age or race and crucially the actor was NOT to impersonate Nixon. That would be disastrous as they wouldn’t be able to keep it up for three days consistently.

It was a painful week in the recording studio. Our actor, Lewis D. Wheeler, was a trooper. Phrase after phrase he repeated, trying to get the rhythm and cadence right. He never tried to put on a Nixon accent except on demand when we all needed some comic relief!

As well as the Nixon fragments, we also recorded 20 full takes of the contingency speech in audio and video. These would be used for Canny to map the mouth movements, and to provide the performance for the new synthetic speech to be produced by Respeecher.

It took three weeks to build the audio model, mainly because all the source audio used to train the model was recorded 50 years ago and was therefore far from ideal. At first it sounded somewhat muffled, so Respeecher experimented with various techniques, including transfer learning, and made some crucial improvements. In the end, we were impressed by how lifelike the synthesized speech sounded.

We got the visuals back from Omer at Canny, and put it all together—audio and video, frame by frame—to form our “complete deepfake”.

Simplified process for creating a “complete deepfake” with audio and visuals. (Credit: Halsey Burgund)

The Zao app, which made headlines in summer 2019, made it seem initially like we’d be able to do this ourselves on our phones, but that was far from reality. It took three months in total to make our six-minute video. That realization has actually been comforting. Making a high quality deepfake still isn’t easy. However, researchers predict that manipulated images and videos that appear “perfectly real” will be possible for everyday people to create within six months to a year.

Even now, the ease of creating a convincing deepfake is a worrisome development in an already troubled media landscape. By making one ourselves, we wanted to show viewers how advanced this technology has become, as well as help them guard against the more sophisticated deepfakes that will no doubt circulate in the near future. If someone who experiences our video later recalls the believability of our piece and, as a result, turns a more critical eye on videos they see pop up in their Facebook feed, we will have been successful.